The Struggles of Everyday Americans: Health, Work, and Survival

Notes from our recent trip to the USA

On work travel to Miami, Florida, and Austin, Texas, last week I learned a great deal about the struggles of ordinary Americans trying to survive in an increasingly hostile, globalised environment shaped by systemic exploitation. In Ubers, salons and cafes, I spoke to many who expressed a growing awareness of the fact that the system disproportionately benefits the few. This was especially evident in conversations with hard-working moms and dads, doing everything they can just to get by.

Most of the people I spoke to told me they had no health insurance. If something went wrong with their health, they faced the crushing reality of having to come up with the money for ambulance and hospital care. A 22-year-old hair stylist I met had suffered a massive uterine haemorrhage just weeks after receiving her one and only COVID shot. She is still paying off a $1,900 emergency room visit—without even receiving a diagnosis or proper treatment. One woman told me that, in her area, unless you have $3,000 for an ambulance, you can receive no medical help at all. She said health insurance would cost her $600 per week alone, without her family.

I heard similar stories about health struggles from others, too. One young woman, also a hair stylist, told me that two of her closest friends, both in their twenties, had been diagnosed with turbo cancers – colon and skin– respectively. Both had taken COVID shots.

The working-class environment seemed exceptionally tough—not just because of the financial strain, but also due to the cutthroat nature of employment practices. One individual was dismissed from his job after being ill for just one day.

With the rise of the gig economy, where people scramble for small, limited opportunities, it felt like a life of constant stress. Many individuals were juggling two or more jobs just to pay the bills. One single mother who drove for Uber shared that a bag of groceries now costs her $120. Another Uber driver told me that Uber takes 50% of the fare, so on an average day, she is lucky to earn $200 after the platform takes its cut.

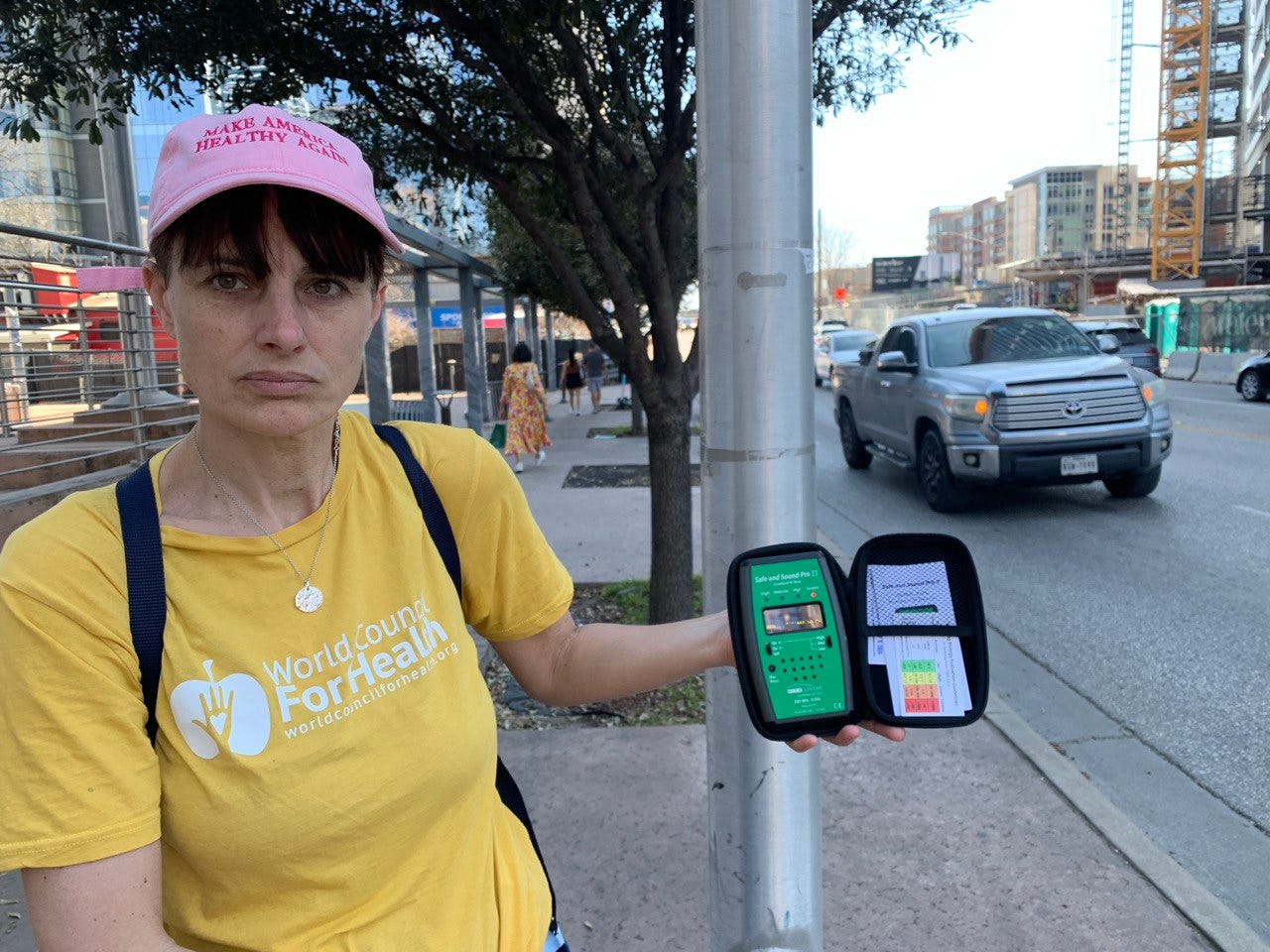

About half of the Uber drivers I spoke with were from other countries. One man told me when I showed him the high EMF reading on my WiFi meter that his mother, who lived in Africa, warned him his mobile phone would give him cancer. We spent some time reflecting on the wisdom of mothers, something that seems increasingly rare these days among young mothers. It’s all too common to see babies distracted by mobile phones, or strollers being used as easy storage for a parent’s device while they walk. The exponential rise of electromagnetic fields due to wireless technology including 5G is a growing concern, especially when it comes to children. Their thinner skulls and smaller, water-heavy bodies make them particularly vulnerable to the health effects of radiation from mobile phones and other EMF pollution in the environment.

While those in low paid positions—like Uber drivers, grocery store cashiers, waiters, and hair stylists—immediately grasped the health risks of mobile phones and wireless technology, the more affluent people I encountered tended to shrug it off as a "necessary evil" for which nothing could be done. I was struck by the stark contrast in attitudes: low paid individuals were eager to learn more and make changes to protect their health, while those more privileged preferred to remain wilfully blind, if not dismissive, of the risks posed by ubiquitous wireless pollution.

The less formal economy also had stories to share about poor health. Sleep deprivation was the most frequently mentioned issue. One Uber driver, whose Honda vehicle registered peaks of 70,000 microwatts per meter squared (µW/m²), told me that he couldn’t sleep and was plagued by images of driving his Uber all night long. He also slept with the phone next to his bed which is not a good idea. After our conversation on the effects of wireless radiation he decided to turn off his phone at night. When I suggested he also try grounding himself by standing barefoot on grass between clients, he recalled that he always felt peaceful when doing so but hadn’t connected the dots before. Our bodies often know what’s best for us—we just need to listen.

I encountered a similar story on a previous visit to Florida. A colleague asked me to check her new home for wireless radiation. I found that the only place in her house with acceptable levels was her dressing room—where she often retired to when she came home because it was the only spot she could think clearly. Once again, it was clear that our bodies instinctively know what’s good for us, if we pay attention.

Another Uber driver in a Tesla electric vehicle, which recorded peaks of over 400,000 microwatts per meter squared, confided that he was experiencing sensory abnormalities—pins and needles in his arm—and ongoing insomnia. This particular driver said his problem had started with the Tesla and, after seeing the Wi-Fi reading, he decided to ask the company for a different car. Interestingly, only one driver I spoke to was getting more than five hours of sleep a night. They really are a high risk group for Wi-Fi intoxication, working in a sea of wireless pollution all day long as they navigate the streets with mobile phone tracking on the Uber app, usually in addition to the car’s GPS navigation system.

One of the most eye-opening experiences came near a junior school surrounded by two massive cellphone towers with multiple 5G antenna. The radiation levels were so high that I felt brain fog, nausea, and chest tightening. My colleague, Nic Robinson, had it much worse—her executive functioning significantly decreased, and she could barely speak. When we left the area, she had little recollection of the time between leaving the towers and returning to the hotel, clearly having gone into fight-or-flight mode.

I plan to follow up with the school because if we experienced such severe symptoms, it’s likely the children and teachers are suffering even more. A health survey of the school seems essential, as one would expect to see behavioural disorders, cognitive issues, and more. This could be a valuable test case.

We had to carefully manage our exposure after that, especially since antennae are regularly placed in lampposts throughout the city of Austin, and massive towers are common in bar and restaurant districts. When we moved to a new accommodation in Austin, we found the hotel Wi-Fi to be incompatible with sleep—it emitted over 300,000 microwatts per meter squared from the smart TV and climate control system. Though the bed was comfortable, it didn’t matter. If you can’t sleep, nothing else matters. The hotel staff kindly disconnected the devices responsible for the radiation and, as a sign of just how over-engineered these hotels are, we were still able to access Wi-Fi from the hotel café, 12 stories below our room!

I try to stay in older hotels, as they’re less likely to be saturated with Wi-Fi, but renovations are turning even these into hubs of digital radiation. We desperately need a website that lists hotels, restaurants, and taxis with low or no Wi-Fi exposure.

As I wrote this on the plane home, sandwiched between two pleasant young men in their twenties with 5G phones, my wireless meter maxed out at 2,500,000 microwatts/m2. I tried to educate them about the risks, but they just chuckled and dismissed my suggestion to put their phones on airplane mode, as if not having Wi-Fi two kilometres above the ground was a crazy idea.

Despite my usual optimism about the dawn of a better world for our children, this trip has left me questioning whether it’s too late for most Americans to escape the wireless prison into which they seem to have sleep-walked. People in countries where the digital infrastructure is not yet so extensive may have more time to wake up, organise and fight back. But the U.S. is vast, and perhaps other cities are different—let me know in the comments if your city is less polluted than Austin.

For now, I’ll focus on the small wins: feisty 22-year-old Izzy at Drybar in downtown Austin, who firmly declared she would never take another vaccine, and the Uber drivers who will turn their phones off at bedtime and ground themselves barefoot between clients.

World Council for Health has many US subscribers so I know there are Americans protecting their health from the after effects of the COVID shots, as well as the dangers of wireless technology. But after this experience I can’t help but wonder: is it too late for the broader population to wake up? Time will tell. In the meantime, please don’t wait for your government to MAHA…

Rather, get going and MYHA…

Make Yourself Healthy Again!

…Sovereignty is key.

Watch this German experiment on the impact of mobile phones on brain activity in cars:

Why do we measure Wi-Fi and EMF in microwatts per meter squared (µW/m²)?

Wi-Fi (and other forms of electromagnetic radiation) is typically measured in microwatts per meter squared (µW/m²) to quantify the intensity or power density of the electromagnetic radiation at a specific location. Here’s why this unit is used:

Power Density: The key idea is to measure how much power (in microwatts) is absorbed by a square meter of space. This helps assess how much electromagnetic energy is reaching a given area, which can be relevant for health studies, device performance, and safety standards.

Electromagnetic Fields: Wi-Fi signals (like other wireless communications) are a type of electromagnetic field (EMF). These fields carry energy, and the intensity of the radiation at a given point depends on how much power is radiated over a certain area. The microwatt is a unit of power, and measuring it per square meter tells you the amount of that power within a specific area in space.

Health and Safety Standards: Scientists and health experts often use this unit when studying the potential health effects of radiation exposure, because it's useful for understanding how much energy someone might be exposed to. Higher power density (measured in microwatts per meter squared) could indicate a greater potential for health effects from long-term exposure to EMF.

Measuring Exposure: Devices like EMF meters use this measurement to detect the strength of the electromagnetic radiation emitted by Wi-Fi routers, cell towers, and other wireless technologies. By quantifying exposure in µW/m², researchers and individuals can assess whether radiation levels are above or below recommended safety limits.

In short, measuring Wi-Fi in microwatts per meter squared gives a standardised way to assess radiation exposure levels, which can help with understanding both health risks and device performance, and is used for comparing safety levels across different environments.

Get REAL facts about wireless radiation on the World Council for Health website

Everything you need to know, all in one place…

Small wins. Our taxi driver in St Lucia had it all. COVID, climate, food, vaccines, masks,PCR tests. He won't eat supermarket meat and raised his own chickens. Very uplifting. He also believed in his God and God given immunity system.

Can you share what meter you use? I’d like to buy one.